People with bodies like mine are manipulated, chastised, and exploited on a daily basis in a world ran and ruined by white supremacy and capitalism. Black people’s vessels have been shaded since the days of slavery where slaves were countlessly used to conduct inhumane science experiments to today where white people think it’s cute to dress up in blackface and mock the figures of our beings. Everyday is a struggle to be beautiful and to rightfully bask in that beauty. As a black queer, I am also constantly confronted with media from condom advertisements to porn that depicts my body as beastly, only good for a wild night and not even worthy if it's too femme or not “fit”.

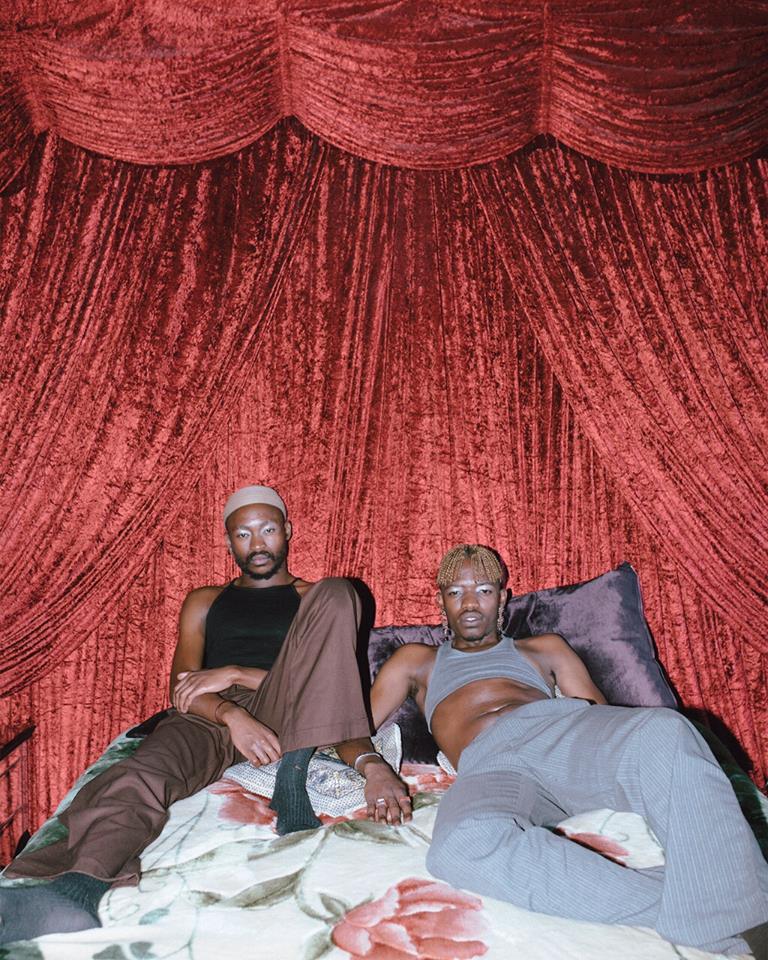

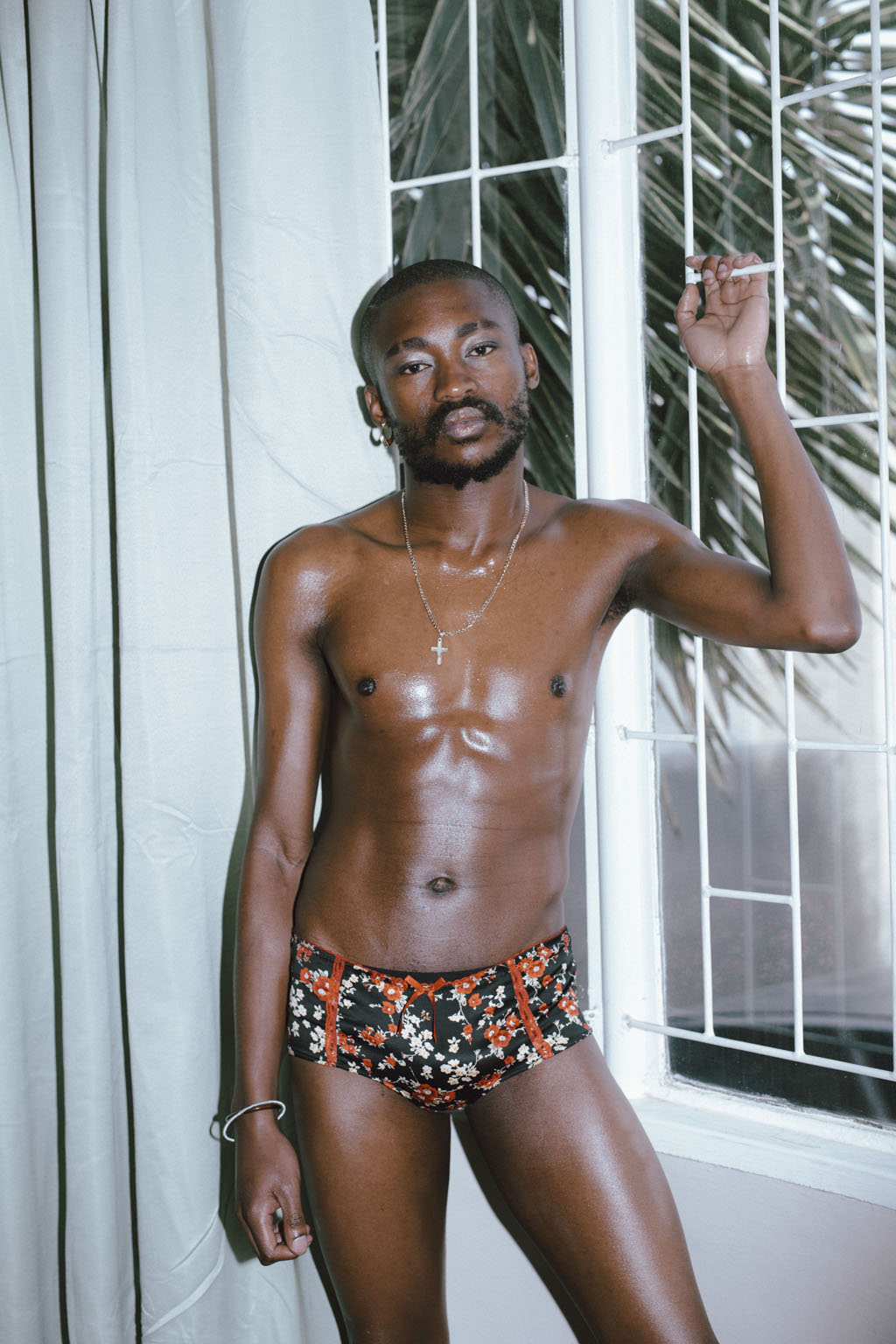

But FAKA, a South African performance art duo, tells me differently. Through their work, I see myself as an enchanted figure with a gold hue that’s structured with brilliance and filled with gifts on top of gifts. Though very soft and cunt, they aggressively confront the societal oppression against black queer bodies via their bodies, which creates a progressively accessible dialogue and interaction between their themes and the world. I spoke to the duo about QTIPOC existence in South Africa, celebrating femininity and finding love as a queer people of color.

FAKA is composed of Fela Gucci and Desire Marea, who both live in Johannesburg. Their work has been featured on AfroPunk, Elle, and OkayAfrica.

From FAKA:

“FAKA in is Zulu means to enter, to penetrate, to occupy. We chose this name to symbolize our intentions of penetrating and communicating silenced themes in the spectrum of black queer identity and also to dismantle the internalized heteronormative righteousness that has contaminated our community with its hierarchy of male privilege. FAKA, in the context of sexual intercourse, is an order given to the perpetrator to penetrate and our ownership of a term linked to the assumption of passivity is a protest to empower the most shamed identities. It is the ‘bottoms revenge.’”

Abdu Mongo Ali: How did FAKA end up expressing through performance art? You do music and video too. How do those mediums help beacon the themes of your work?

FAKA: A lot of the things that we express stem from the displacement of our bodies on the counts of race and sexual identity in a system that heavily operates through racialized hetero-patriarchal constructs. Performance came naturally to us as it puts our bodies, our immediate space, at the forefront of a bigger discussion about how our bodies intersect with the spaces we occupy. Performance is a form of resisting all these ideas that try to keep us oppressed. Music is what we first experimented with and seemed like the truest way to communicate our ideas.

I want to jump right into the theme of humanization because I am reading Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of The Oppressed” which speaks about how the oppressed are dehumanized and how liberation must involve the humanization of the oppressed.

Humanizing black queers to us means speaking openly about our existence and not allowing ourselves to be processed under the oppressive heteronormative gaze. Telling our stories without shame and knowing that they are valid. This is important to us because for a long time we’ve shamed ourselves for the way that we exist but, through learning about oppressive ideas and the structures that support and perpetuate them, we are constantly choosing to unlearn and hope to connect what we learn with our community as it continues to operate through oppressive ideals that say “you are nasty. So, humanizing black queers looks like liberation learned through self-actualization.

How has humanizing black queers changed due to the influx of the other reality: the internet? Does the influence of digital socialization have a radical effect on both dehumanizing and humanizing the black queer body, spirit, and mind?

The internet is working as an empowering tool for the black queer body. Of course, there are spaces within the digital sphere that work to dehumanize the black queer body but, ultimately, we are owning our existence in the digital space whether it is through posting a selfie or sharing our experiences through twitter, we are being visible to the world.

What is the Black queer body? Who birthed it? Who owns it? Where does it stand today?

The Black queer body is transcendental, it belongs to the spirit and mind of the individual who claims it and that individual is a liberated being who’s forced to navigate a world that tries to keep it silenced but it resists because it is self-actualized.

Gender to us is the fluidity of self-actualization, defining for one’s self is a way to exist in the world away from the behavioral constructs that are forcefully assigned to us when we come into the world that say you are either a man or woman. It is important to redefine gender to allow for non-binary realities to freely exist in the world, so that it's okay for all dimensions of love to exist.

Black queers often celebrate femininity within their bodies, minds, movements, spirits. I feel like some of your work's mission is about fighting against the debasing of femininity. Why do you think society has made sure to oppress femininity and how does feminine empowerment change the interaction between society and black GLBTQ?

Femininity is a demonized idea because it is perceived as submissive. This is a result of patriarchy, which teaches that the feminine has no power. Within the queer community, someone who identifies as fem is easily slut shamed. They are told that their bodies hold no value if not affirmed by heteronormative aesthetics. This shaming of femininity is more brutal in online spaces that are designated to help queer people find love or sex or any contact we desire. 16-year-old queer people are exposed to the profiles that violently state "No Fems and No Fats," and we feel that by expressing our femininity the way we do, we are not only fighting a genocide against femininity in our community but we are liberating those who feel unsafe and unlovable expressing their femininity.

What is it like being QTIPOC in South Africa? How do both heterosexual black folk and white people interact with South African QTIPOC?

Although the constitution claims to protect the rights of QTIPOC in South Africa, the reality proves otherwise. Hate crimes are often left unattended due to the deeply internalized homophobia that prevails in the country. Our lives are not treated with dignity as we do not fall under the dogma of religion or supposed African beliefs that were alternated by colonialism, demonizing queerness. Either black communities like townships can be free or violent spaces for QPOC. There are cases where the community does not react negatively but also there have been many incidents where QPOC have died from severe hate crimes. At some point, there was a massacre on black lesbian women in townships. A lot of these cases were not followed. This proves how unsafe it is, and white communities either fetishize or reject QTIPOC; if you’re not the model citizen, token QTIPOC, then you’re an intruder.

It is difficult to exist in spaces like school or workplaces where the oppressive force of heteronormativity rules. There are supportive structures that exist to assist queer persons but sometimes that's an issue of accessibility. As a QPOC from the township, you may stand at a disadvantage.

Also, there isn't enough visibility of black trans folk and this may be due to the fact that the majority of the people in the country are uninformed about trans issues or what it even means to be trans. Even within the queer community, trans lives are overlooked; there is a stronger focus on gay or lesbian issues. Our work celebrates trans identities in the way that we shamelessly explore our limitless queer identities, affirming resistance through self-actualization.

This is a bit off topic but is important to you to showcase the myriads of black queer relationships, specifically love relationships? Do you think it's hard for black queers to find love and be in relationships? I see being in love, loving yourself, and being in a relationship almost sort of a privilege that I see white gay people being able to access but not for QTIPOCS.

Finding love as a queer person of color could mean many things. You may find love in community or nightlife. Romantically speaking, it is a bit of a challenge as often there’s a recycling of heteronormative ideals that prevent us from loving each other. We are also still dealing with a lot of childhood trauma experienced from suppressing our identities. The lack of visibility of queer lives hasn't allowed us to have tangible references of what it could mean for queer people to love each other romantically. The concept of self-love does, at times, come under the umbrella of privilege, considering the prevalence of poverty that may force some queer people into sex work - these kind of situations need us to question the concept of self-love -- that maybe it may exist in a way that doesn't dehumanize the survivor.

What are your goals as FAKA and how far are you willing to go to fulfill your mission?

Our mission as FAKA is to teach complexities, to create visibility, to humanize and we are willing to go as far as the distance.

For more of FAKA’s work, visit faka-blog.tumblr.com and follow both Fela & Desire on Twitter.

Like Faka on Facebook as well.