Words by: Lawrence Burney

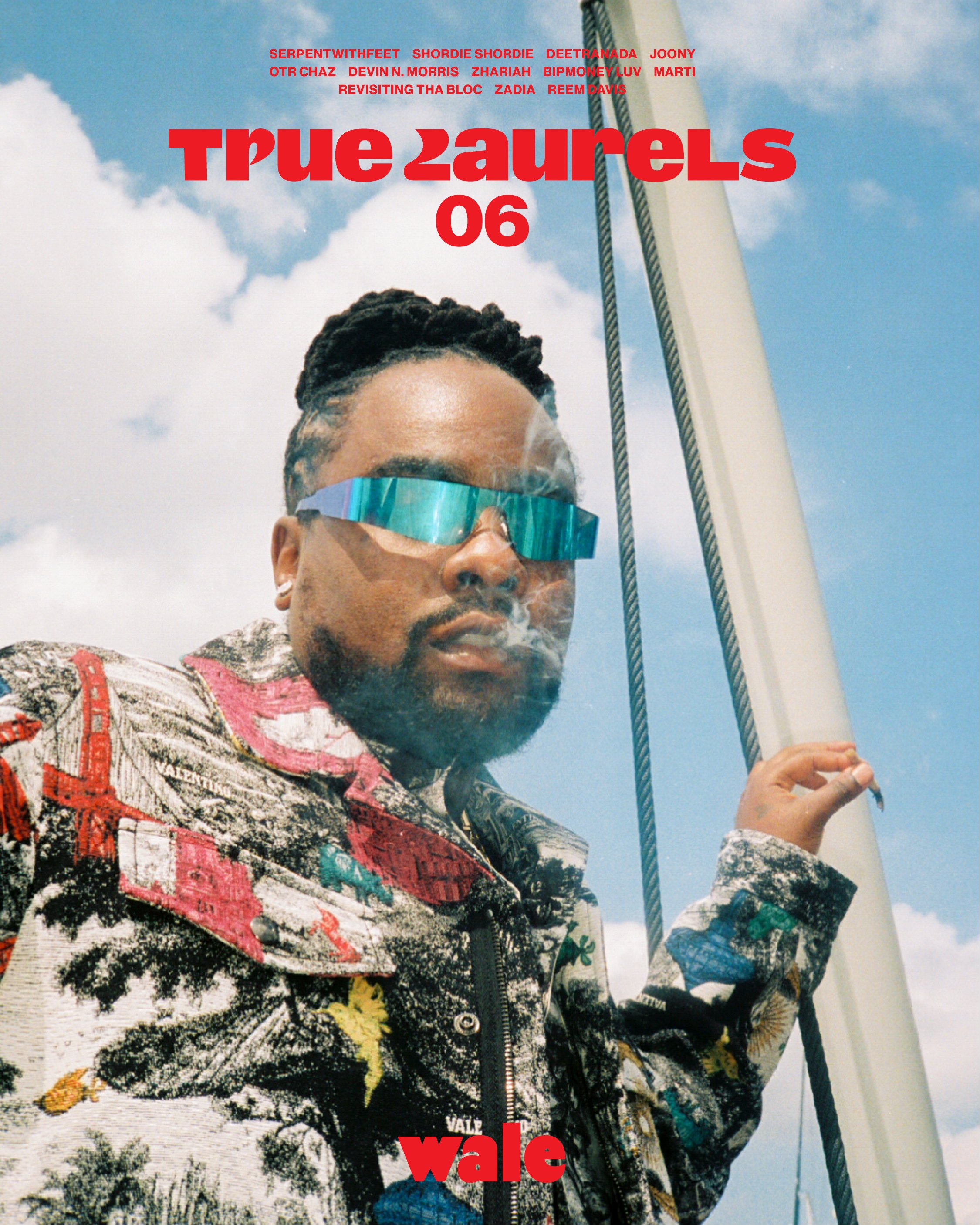

Photos by: Kyna Uwaeme

For me, Wale’s story continues to be one of the most interesting in rap music because, for many years, I’ve felt like he sort of operates in a perpetual state of limbo. His skills are undeniable. He’s in constant radio and nightclub rotation year after year with catchy songs that keep his name in the mix. If he didn’t explode onto the national stage like he did in the late 2000s, then the DMV rap scene would probably not have produced as many hopeful stars as it has in the years since. There were early co-signs from JAY-Z, and other hip-hop legends. He’s been Grammy nominated. And, as it stands right now, he’s the most important rap artist to ever come from the DC area. It’s even more special that he got to where he is, partially, because he was masterful at joining rap with the formerly-dominant homegrown go-go, making it palatable to the mainstream in ways that it hadn’t been before. But that’s not enough for him.

Wale wants to be considered along with the greats of his class — the Holy Trifecta of artists who carried the rap ethos of the 90s and 2000s over into the internet age: Kendrick Lamar, Drake, and J Cole. What self-respecting artist from that generation wouldn’t want to be mentioned in those circles? Shit, even artists like Wiz Khalifa and Kid Cudi have dedicated international cult followings. But where things have gotten tricky for the DMV titan is when he’s had contentious ways of expressing the frustration of feeling like he’s being underestimated. And undervalued. There’s no need to get muddled in the specifics. Anyone who’s been on the rap internet for the past decade can attest to the fiery — sometimes head-scratching — debates Wale’s gotten into with complete randoms about how he’s an elite spitter or when he tries to prove that he hasn’t gone Hollywood on DMV artists trying to climb the ladder. The rants, digs at other artists, and what people perceive as whining about support has surely turned some off to the point of no return. And that probably stings for him. Especially considering that the majority of those moments came more than four-five years ago — when he says he wasn’t in the best emotional space — and are still thrown in his face as if that’s the type of time he’s on at every waking moment.

Wale has made plenty of iconic music moments. “Work” from his 100 Miles & Running mixtape during my high school days still gets the occasional listen. He was possessed on that. His Seinfeld-inspired About Nothing series was one of the best executed rap concepts over the past decade, joining social commentary and comedy into the themes of his songs. “The Bmore Club Slam” produced by Baltimore Club legend Scottie B from that series’ inaugural installment is what made me become an early fan. That track’s opening seconds, where Wale denounces the DC vs Baltimore rivalry and criticizes Baltimore station 92Q for not playing his music, are proof that he’s never shied away from advocating for himself. Ambition felt like he was being molded for superstardom under Rick Ross’s MMG label. A more recent favorite is “June 5th/QueenZnGodZ” from his short 2020 EP, The Imperfect Storm, which was largely inspired by the wave of unrest in response to George Floyd’s killing that year. On it, he talks about the frustration associated with America’s anti-Blackness, pointing out that his daughter had to witness killings by police while scrolling social media. There’s plenty that makes Wale appealing, but there’s also something that often feels vacant in the music and the marketing.

Every one of the peers that he wants to be in association with have something that anchors them. Drake is unrepentant in his love for cheesy, over-the-top theatrics and has never ran away from being made into internet punchlines. He actually uses them to his advantage when crafting his endless Instagram caption bars. Kendrick Lamar assumed the role of a Nas for millennials: the dude with street ties who didn’t fully jump into that water, but has firsthand accounts of the ramifications that come from that lifestyle and how it affects a generation of kids who can’t escape their affiliations. J. Cole is an everyman whose subject matter hasn’t really changed much since he was a college-aged kid trying to make it. His commitment to being “normal” will help him appeal to 18-25-year-olds for eternity. It’s hard to say what Wale’s hook is. He’s huge with HBCU-adjacent crowds, always has a song on radio, and can rap with anyone, but the music isn’t always vulnerable in a way that makes you feel like you have a deep understanding of him. It’s a feeling more than anything. And, of late, the music feels like it’s almost too on-trend, making sure it hits all the spots to get spins. That seems to be the constant dilemma he finds himself in. How does he, as a decade-plus veteran, breakthrough to the crowds he really wants respect from while making sure he doesn’t fade away commercially? I’m not sure what the answers are.

During the late summer of 2020, when it felt like the pandemic was maybe coming to an end (we were very wrong), Wale invited me to a couple studio sessions in LA for what I believe turned out to be a couple tracks from his latest album, Folarin II. We talked about how he’s judged by rap fans, the impossible standard he’s held to by the DMV, his desire to reach more people, and the never ending hunger to prove himself.

You’ve been talking about trying to make a perfect album, or feeling like you got to present perfect shit to be considered. But do you feel like perfection is something worth trying to attain? Or is it more like you just feel like somebody is ready to pick apart any type of deficiencies you might have?

Yes. And I think that anything that I do wrong — I make music for everybody. But for some reason, I can't get it to everybody. And that sometimes frustrates me. And I may not be open about that. But I've been trying to get a different perspective on that shit and not be negative. It's just like, man, I gotta find a way to get it to everybody. Because a lot of people know I've been doing this for sometime. A lot of people don't know. And I want to be in those conversations because I work hard on this shit.

Maybe it's a social media thing that clouds people’s judgment of you.

I'm really grateful for everything I got. But at the same time, I want to be great too. Nigga, I want to be better, to be honest with you. I know I've done great things, and I've done amazing things. But I still love the art form. I want to still be in the conversation of niggas that I grew up idolizing. I’m in the second quarter of this shit.

Second quarter of your career you mean?

I think so. I’m getting to my seventh album.

What does that second career phase look like for you?

I don't know. I want to be one of the leaders of this shit. As far as the direction the culture is going in. The knowledge I've obtained. I want to be able to still be part of it because I enjoy hip-hop, I love it. You feel me?

Do you not feel like you're regarded in that way?

Um, yeah. But it's just like you gotta keep pushing yourself. You gotta keep doing it, otherwise it's going to be like, whatever. But also at the same time, I still want to keep getting better as an artist. I really want to be better as an artist. I want to learn from other niggas. That's why I talk to Thug, I talk to Durk, I talk to niggas around the way just to ask what they think of what’s going on. Because I want to get better, as everything. As an artist, as an entrepreneur, as a producer, song writing. You see all this shit. I want to get better at everything. I've always been into it, but now I just want to get way better at everything. And I think I've been able to show that with my last album. Now it's like okay, what now? And that's where I'm at. Get to it.

Wow…That's Crazy is one of my favorite projects you put out. Not even just recently, in general. It’s super solid.

I appreciate that. I think that's my best project. But you know, somewhere along the line, I lost the people, maybe. When physical sales was popping, I was always in the top ten. But it is what it is. At this point, I just be like, I want them to hear me. Because I know what I mean to a lot of niggas whether they are in the industry, whether they are just from DC and they've seen it all come up. And I wear that as a badge of honor. I want to make them proud too. Even my biggest critics will begrudgingly fuck with a nigga. And I like that. I want to make everybody from home and everybody from early on to be like damn, I've been here from the long run. From beginning to now. At the same time, I still want to be great. I talk about it all the time. If you listen to songs like “88,” “Legendary” and shit like that.

I think something that's really interesting about your career in general, as opposed to a lot of your peers, is that you’ve made legendary strides on the mainstream level, but you really gave light to a whole fucking region.

Yeah, but sometimes when I say it, people be—

It's just a simple fact. It's not even a debate.

It's just weird, though. I was really young when I came into it. The older people [at home] were like, “We been doing this” and the young niggas was like, “You a rap nigga. This is go-go. We ain’t thinking about that.”

Right.

It's tricky. Sometimes I be like, I ain’t do enough. It's like imposter syndrome. That's what they call it when you're like, why am I here? I don't deserve to be here. Even my baby muva, one time, she was like, "Nigga, you're the first nigga from DC." Even if we’d be arguing and she'd be like, "Nigga you did that for real." But I got to remember that shit, bro. It ain't all the time. It's not all that time.

Do you feel like you gotta consciously remind yourself of what you’ve done?

I don't know, man. I feel like somedays I do. But you know what it is? I got good friends. I got friends like Thug and Cole and Flex and Ade. I got friends that be reminding me. That helped a little bit. It helps. It definitely helps.

Just to know it's just not internal?

Yeah, that helps. It's like, bro, all I want to be great and rep this whole DMV shit. That's all I want to do, put on for niggas that was like me. I never was pressed to be no street nigga. That was always me. Not only my circle, but I represent the niggas like that. And also, children of immigrants. My father drove a cab. My mother worked odd jobs, nursing and everything. We lived in a one bedroom apartment in Northwest. And I remember being robbed on the 4th of July. Somebody ran in our shit. I remember my brother used to fall off the bunk bed and wake everybody up. All types of shit like that.

I think about that. I think about how far I came. I think about, bro, there was a point when nobody thought there would be a rapper from DC. And I did that. But also, as somebody that came up under Jay, up under Ross, I'm like, am I doing it right? Am I helping? Because it will always be like, you don't help [the DMV] and I'm literally trying! You've been with me for two days and you see, I'm trying to get everybody to come through, show love to niggas, and blah blah. I'm trying bro.

We lightly touched on it, but that topic tends to come in waves. It's like you know it’s going to happen every six months. Somebody gonna post about Wale not helping the DMV.

I just don't understand why that narrative exists. Even somebody is going to read this shit and be like, who he help? And it's like, bro. It's just that the people I help, they may not be as passionate about saying, “He helped me,” as I am about defending my own name. And that's cool too. That's fine. That's very, very fine. But I don't know man. I love the DMV so much. I’ve spent time in the studio with Tate Kobang, Rico Nasty came to my old studio before she blew up, me and Shy Glizzy did the “Southside” joint early on.

As you continue moving forward and continue to stamp a legacy, how do you start to track your success at this point of your career?

I really can’t track my success. I really can’t bro. I just go in, I do the work and come up with the ideas. I did a freestyle the other day about just being fearful and how I don't trust nobody and shit like that. That's how — right now, in this moment — how I feel. I'm scared of people. I don't trust nobody. I'm so uncomfortable. I'm paranoid. I saw Nipsey die on my Instagram. So I got things in my mind. I'm not all the way right. So, I try. But it’s not a layup at all.

Do you get into modes where it's like, this is a particular theme that I'm operating in right now, but that don't mean this album is particularly going to be just this? And I don't even mean just sound. I mean a general mode or something that's on your heart as you’re recording.

That was like The Imperfect Storm. Right now I'm recollecting, it could be something previous. There's no urgency for me to talk about today. And Imperfect Storm was urgent. Everything is right now. Getting your mind back off that and getting into album mode, that's why I really don't have an idea. I'm just trying to make everything as good as I can. But it's like bro, I hear Imperfect Storm was flawless, it's perfect. It's my best EP I've ever put out, and it's my most recent project. That should show you musically where I'm at. But it just didn't reach the people it was supposed to reach. I know in my heart of hearts. I wanted to make a project in real time. I want people to know what I'm thinking, how I feel.