Words by Lawrence Burney

Photos courtesy of t.p. Luce’s archive

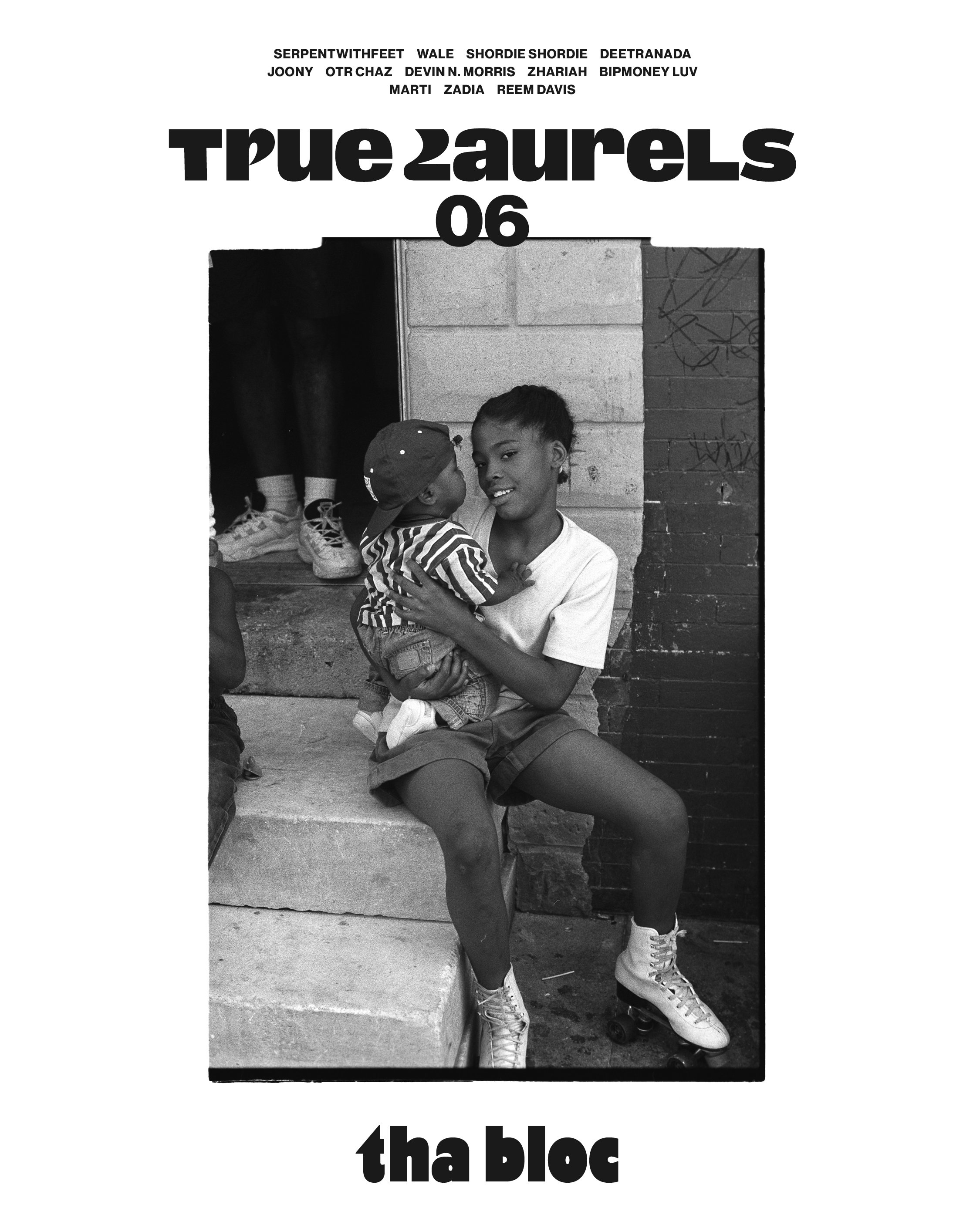

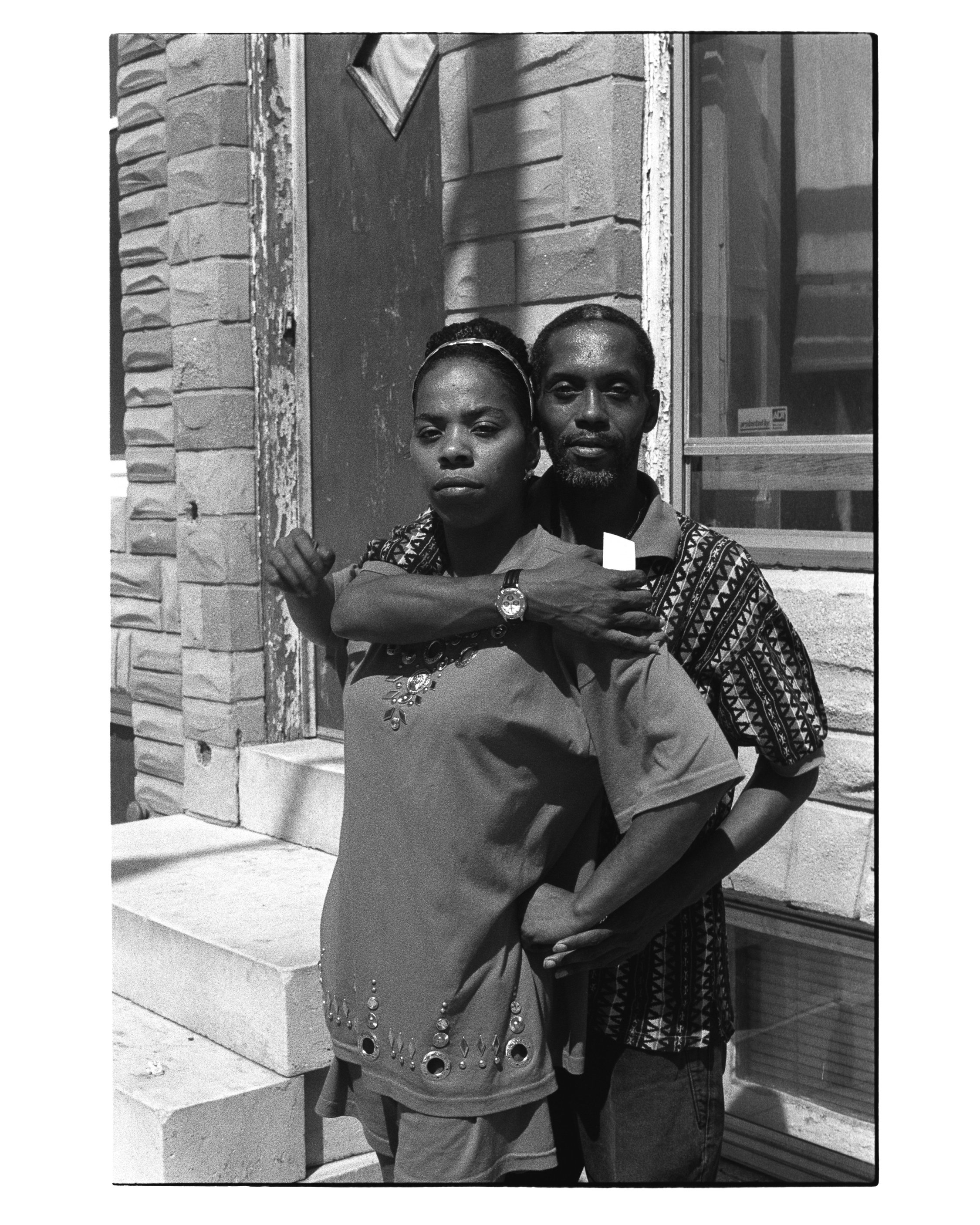

In 2004, one of the most important pieces of East Baltimore documentation was released when t.p. Luce’s Tha Bloc: Words, Photographs and Baltimore City in Black White and Gray was published. In it are beautifully-shot black and white photos (captured between 1995 and 2003) of people living their everyday lives: getting ready for church, loving on each other, shooting dice on the porch, playing video games with extension cords coming from inside the house. There’s poetry inspired by the people you see. But really, the poetry goes beyond the specific faces of growing children, adolescents carrying pistols, and adults holding things together. These words offer commentary on the circumstances that many of these characters find themselves in as a community. Most are spending the majority of their time working and making a way for their families. Leisure is hardly achieved. Growing boys are emotionally and mentally hardened before they reach high school age. Shallow political campaigns half-heartedly attempt at placing bandaids over gaping wounds. Tha Bloc is just as much an assessment of the things wrong with American society as it is one of the specific neighborhood that t.p. Luce lives in. And it’s so spot on — equal parts uncomfortable, heartwarming, and matter-of-fact — that it makes me wish there were more just like it.

This book holds a special place in my heart because most of it is shot on Ramona Avenue, a street in Northeast Baltimore’s Belair-Edison neighborhood. My family lived on this block from the time I was 9 until about 15. A lot of the people photographed are people I saw everyday. I’ve known some since elementary school and some I still rock with today. And to make it even crazier, t.p. Luce is the father of one of my closest friends. Curiously enough, I don’t remember seeing t.p. around when I was a kid. The majority of the book was shot on the 3300 block of Ramona Avenue and I stayed on the 3200 block, which are only a few steps away from each other. Part of me wishes I could rewind the clock and cross paths with t.p. as a kid so my younger self could be immortalized in the project, but coming across it in my young adulthood felt like such a divine connection that the FOMO doesn’t strike as strong as it could.

When I finally found out about it, I was transfixed with it. I knew that he was originally from New Orleans, went to college in New York City, and moved to Ramona Avenue when his kids were very young. But I had so many more questions: Why’d he move to Baltimore? Why this neighborhood? Why was Tha Bloc made? Who was it intended for? Why don’t more people know about it? Over the years, I’d only spoken to t.p. about it in passing. But I was finally lucky enough to sit down with him to learn about the origins of the project, its legacy, and how he feels about it now that it’s almost 20 years old in depth. And even better is that he allowed me to dig through his archive of photos from the project (some that made the book and more that didn’t) and share them for this story. The majority have never been seen by the public.

What drew you to Baltimore and, specifically, this neighborhood initially?

One of the things that made me move to the city was economics, in the sense that I didn't want to go back down south and I wanted to live somewhere where you could afford a house with a yard for a reasonable amount of money. That's actually what I'm thinking about at the time. And when we moved here, to this neighborhood, it was because the house was available. It was not because this block was mostly Black because it wasn't. From all these houses, I would say two were Black couples. All these houses were white people. I didn't know at the time, I figured it out later, but they were all old Polish immigrants. The majority of them were Polish immigrants. There was still some people, other white people who lived here who were newer. And so years later, it was literally White Flight in real time. And I watched it happen. And that's sort of what started Tha Bloc — watching people just literally flee.

Because Black people were coming.

Because Black people came. Well it was one particular episode and that is, they blew up the Flag House Courts. When they blew up the Flag Houses, within two weeks of those Flag Houses blowing up, this whole area changed. Because people, literally, whenever they moved the people out, a percentage of them were left to their own devices. And it appeared that they just walked over here. So, I used to see people all of a sudden on Belair Road. And I'm seeing all these people just meandering. I'm like, "The hell's going on?" And all of a sudden, Belair Road became a strip for a minute. There was prostitutes working Belair road. And I'm like, "What just happened?"

In the span of, what? A year?

I don't know. I mean, it was less than a year. This was the mid-90s. I'm thinking like '93, some of this was in '93, '94. And then, all of a sudden people started moving out. What happened is the people from the Flag Houses, they started moving in here under — I don't know what — I would assume Section 8. I don't know. I mean, just all of a sudden, boom, boom, boom. And they weren't homeowners, they were renters. Here, here, here. And that happened within a year. All of a sudden, you started seeing white folks were just leaving. Now, the old guy here, Mr. Carl, he didn't leave. Him and his wife stayed there and he talked to me about this. "I'm not going anywhere. I think you're fine here. I like all the people around here. All these people telling me I'm going to leave. My kids come and say, 'Oh, you going to leave?’'' He says, "I'm not going anywhere." And he told a lot of funny stories, too. And he actually died there. Because he had to be in his late 70s at the time. His wife died, and he died three months later.

When my family moved on the 3200 block, that was 2000, or 2001. But, it was all Black. It was already all Black.

No. Yeah. It became black.

We had one white guy that lived on our block that was old. Had to be like 80-something. And we just called him Pops, or something like that. And he had an American flag on his porch. I think he was in the military, or something, at one point. But, he was literally the only white person. He was in the middle of the block, on the right hand side.

There was a couple here. I called them the holdovers. There's a couple of holdovers. Carl was one of them. It was an old guy over here. Three, four, doors down. Never came outside. He used to look out the window. Kids were playing around. And I remember one time, I saw him, and he would sit in the window. And he would look at the kids playing. He would be there all day. And I would look up at him, and he would just look around. Never said anything. He didn't complain.

So, in effect, Tha Bloc started out as a project documenting this change in the neighborhood?

That's how it started off. And when I saw the kids — because I was already looking for a project because I graduated from NYU in photography — I was looking for a project, and there it is. So, I just started photographing them.

Were people receptive from the jump?

Yeah. The kids were, in the beginning. Some of the adults were. But, it was all like, "What you doing? What are you going to do with those pictures? Are they going to be in a magazine?" I'm like, they're not going to be in a magazine. And it went on for a long time. I think the book was published in 2004. I started photographing in '95/'96. Because I didn't know exactly what I was going to do. I was just photographing. And it was really in the late '90s that the project started to come into focus. And I just continued to photograph. And actually, most people got tired of me because I told them I was working on a book. There were guys that used to say that. "Yo, where's the book? Where's this book you talking about?" Because it's been years. We had kids literally grew up with me taking pictures. And they were getting ready to graduate high school. "Where's this book you talking about?" So, I told them. I said, it doesn't work like that. But I said, "I'm going to get to it." And they said, "I don't think you're writing no book. You doing something with these pictures. I don't know. You might be a fed." I'm like, a fed? I said, "Is the reason you think I'm a fed, because you don't know what a fed looks like?"

I just got to know the guys. I got to know them all. It became self-evident. A lot of it reminded me of growing up around kids. You know like, “Oh, this guy's a criminal. He's not a criminal.” All the bad characters. And I'll talk to them. I tried to. I couldn't do a lot for them. I could just do what I could do. I began to understand what I could do, and during that project. And I've been working at that ever since.

What did you feel like that was?

Well, I mean, in addition to being a photography major, I was a history major. I studied history and economics. So I didn't really understand at that moment in time, what the ghetto was in the form of, what I call a technical representation, until I did that project. That was the first time I realized, "Oh, that's what it is." Because what we do is when people think of poor neighborhoods like ghettos, most of the time, think of the shit off of television. It’s what I call a cartoon version of something, not the thing itself. But there's something underneath it. There's a mechanism, and the mechanism is not glorified. It's not sexy. It's not that interesting. What is that mechanism? That was the first time I came in contact with that mechanism, with an element of that mechanism, and I've been working on it ever since. I have a much better understanding of what it is. But part of me, what the struggle was with the project, was that I was playing around with mythologies, with caricatures.

Of the people you photographed?

Well about the people and the caricatures of themselves. It's like, there was so much imitation going on. It coincided with a bunch of stuff that I was studying outside of that project, about the role imitation plays in how you choose your primary association, both conscious imitation and subconscious imitation. Like a subconscious imitation is how we speak until it's conscious, but it's mostly subconscious. When we grow up, we sound like the people we grew up around. Because that's how the brain works. Nobody goes to a talking teacher. You learn to talk and you sound like the people, with few exceptions.

When you look at Baltimore now, in what ways do you feel like it's different? I mean, actually, not even just Baltimore. This block, in particular.

This shit, it's really more or less the same. I mean, there's less kids, at that moment in time-

There's way less kids.

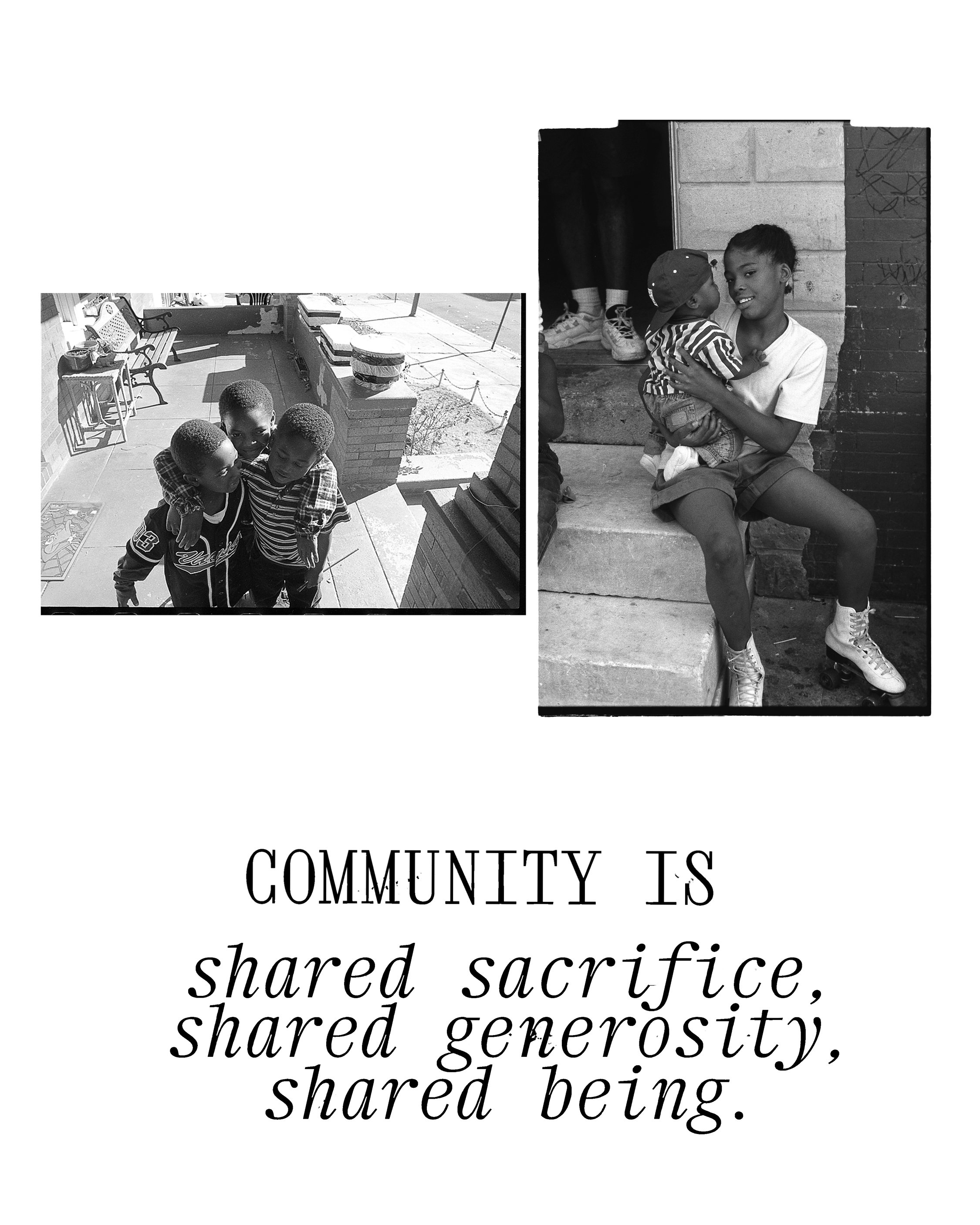

At that moment in time, there was hella kids everywhere. Kids all over the damn place. There's less kids. But, I mean, I don't know. It's just, to me, all the problems that I think we're facing is that, I think, the community is just breaking down. I've watched the communities break down. I watched this one — to the degree that it was together. It broke down. I didn't know that's what was happening at the time. When I looked back at it, I understood why. I now understand why it broke down. People have to — what makes a community is the kinetic energy of the commons. And what sits at the center of the commons is some form of commerce. If you don't have that, then you just have a neighborhood. You don't have a community. Because community is shared sacrifice, shared generosity, shared being. It is: “I am with you today. I will be with you tomorrow. I am going to travel with you, as you will travel with me. I am your people, and your people are my people.” In a real sense. In a sense that we have common action. What we have is, we just have common geography. There's no common action. There's no common being.

Do you feel like it was a community here at one point?

Oh, there was. But, the thing about it is that, what breathed life into the community was the commercial center. And the commercial center was the plant at Sparrows Point. And when Sparrows Point went away, and the pension got looted, the shit fell apart. That's why Pigtown looks like Pigtown. That's why those white folks, they moved out to White Marsh. That's why White Marsh is borderline white trash out there. That shit's crazy. People couldn't find themselves together. They couldn't do it. Part of it is going to be economic. But, the other part of it is that we, as America, became comfortable with the centralized economic infrastructure. That post-World War II. That was America.

Those old communities, they didn't completely go away. They mostly went away. And the communities supported by the economic infrastructure, they became — I refer to them, and this is probably not the best — sort of corporate communities. Not because the communities had corporate people, it's just it was supported by the corporation. And once the corporation went away, they fell apart. This fell apart. Because when I moved over here, I coached little league over at Gardenville. And that was 50/50. It was half black, half white. But, you could still see it was a community. The people still worked at the plant. They still had those jobs. The mothers came, they volunteered, the rec made money. They sold hot dogs, popcorn. They had the bull roast over at St. Anthony's. The bull roast at St. Anthony's, the City Councilman showed up, the Fire Chief, the Police Chief, everybody showed up. Father so-and-so from St. Anthony's. That was it. That's all gone. That's gone, gone, gone. I think the rec is still there. But it doesn't function.

What was people’s perception of you starting Tha Bloc?

There was one old lady who used to say, "I don't know why you hang out with those kids all the time, they're nothing but trouble." I said, I don't hang out with them. They hang out with me. I'm not going with them. They come with me. I don't go over there. They come over here. I was trying to help them out as best I could. And some of them understood that. Most of them didn't. I mean, some of them did, but I wasn't really prepared to do anything for them. I understood what their problems were, but I couldn't do anything.

Did that come with feelings of defeat at times?

No because, once again, I'm from Louisiana. My dad would always say, "Shit is what it is." I remember one time when I was a kid, it was one of those days, man. I was like in the third or fourth grade. Everything went wrong. My bike chain broke. So I had to roll my bike all the way back to my house. And then my tire was running out of air. So I brought it over to Mr. Bossy at the gas station to fill it up with air. The fucking tube pops. So I walk my bike back to my house and I just pushed the shit down. And I said to him, I said, "Man, why is all this happening to me today? Why me?" And my dad looked at me, he said, "Why not you? Who are you? Who are you for shit not to happen to you? Shit happens to people all the time. There's some shit happening around the world right now way worse than this." I don't pity people. I don't feel sorry. I don't do that. It's like every day, man.

Did you have particular aspirations for it once it got published?

I mean, I was just going to do whatever I tried to do with it. You know? I wanted it to be a gallery show, which I got.

Where was the show?

I had a couple of shows. I had one at the African American Museum in Philly. It was a small part of another larger show. Had one at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, a part of a larger show. But I had a solo show at Anacostia, DC. And that worked out real nice. I wanted to do more gallery events, but it was too difficult. Because it's like a lot of things, man. Doing artwork at the bottom without playing the big game, it's too hard. It's too hard to make money.

Yeah. It's extremely hard.

You can't really make money doing that. And I had my kids to deal with. There was no way I had the flexibility. Don't have the money to say, "Okay, well, I'm going to tour this and I'm going to go all..." There was no way I could do it. There was some opportunities, but they weren't enough.

You say you started shooting projects after Tha Bloc that never came out. Did you already have a clear-cut concept on what your next projects were?

Yeah.

Were they related to the concept of Tha Bloc?

Well, they were in a way, but the relationship would've been too abstract for people. And I'm still going to finish them. I mean, I got two books I'm getting ready to do now. One, soon as I hook that printer back up, I'm going to print my temps up. You know? I've been waylaid too much by life events. You know what I mean? It is very difficult, because I don't rely on any of the projects to make money. So consequently, I don't have deadlines. And as events happen around me, it becomes less and less of a priority. But it's going to become more and more of a priority very shortly. Then I'm going to spend a whole hell of a lot more time doing that than I have been. I've had a couple of projects in Baltimore that I could never really pull off in the pandemic. I had to say, "I got to wait this out." But I'm still there. I still got a lot more to do.